We plead against carbon plates in running shoes

The Standing Commission on Vaccination (STIKO) weighs up the benefits and risks of vaccines. If it were to do the same for technical innovations in running shoes such as carbon plates, some models might not be on retailers' shelves.

The Tokyo Olympics that just ended weren't just a lineup of top athletes who did incredible things. It was also an incredible array of technique. After Karsten Warholm broke the 46-second sound barrier in his 400-meter hurdles race with a time of 45.94 seconds, pulverizing the previous world record by 76 hundredths, he said into the microphones of the assembled world press to the delight of his outfitter, Puma: "The shoe helps me have energy longer."

"The secret of the flood of records in Tokyo," was the headline in the German newspaper Welt. And the "Kölner Express" read: "Track and field world records thanks to miracle shoe?" The "energy" Warholm is talking about comes from a thin plate of carbon that runs through the entire midsole in a slightly curved shape. Back in 2017, Nike unveiled the "Vaporfly 4%," a new type of running shoe with a carbon plate that was supposed to make it possible to run the first marathon in less than two hours. Just two years later, 86 percent of the podium finishes at the six World Marathon Majors were captured by runners wearing a Nike Vaporfly with carbon plates in the midsole.

The law of leverage adapted to running shoes

In fact, the idea of Nike's chief developer Matt Nurse to install a carbon plate in a running shoe and thus help runners achieve new best times is based on pure physics. At its core, the idea is to waste as little mechanical energy as possible in the drive phase. Previously, one of the world's most respected biomechanics experts, Benno M. Nigg, together with other colleagues, had demonstrated in a study that considerably more energy is absorbed by the metatarsal bones during the propulsion phase than is produced. In contrast, other joints such as the ankle, knee or hip generate more energy than they consume.

Starting here to improve runners' performance makes perfect sense. The stiff carbon plate in the shoe extends the lever in the propulsion phase, prevents the toes from bending upward (dorsiflexion) and thus avoids unnecessary energy loss. The only problem is: every runner is different. In a study, kinesiologists Darren Stefanyshyn and Ciro Fusco concluded that actually every runner needs a different amount of stiffening to achieve personal best times, depending on weight, height and strength. In some runners, the carbon plates even had completely negative effects.

Only 1 percent of runners need to run 4 percent faster

But almost more importantly, 99 percent of runners are not professional runners at all. They run in their free time to do something good for themselves and their bodies - and not to beat one personal best after another. But who's going to say no when the running shoe industry suggests: Use this Performance Enhancing Element - and get four percent faster. The fact that this technical doping also entails health risks, on the other hand, will not be heard from any marketing department.

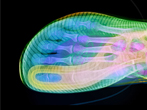

Mother Nature has created a true masterpiece of engineering with the human foot. Think of the foot as a kind of twisted, spring-like plate with toes attached at the front to anchor the plate to the ground. When the foot touches the ground, the plate untwists and elongates to absorb the impact, causing the plantar fascia to pull the toes into the ground (reverse windlass mechanism), anchoring the foot and providing a stable base. As the runner's weight begins to move over the foot, the heel lifts off the ground, using the toe joints as pivot points (the windlass mechanism). Now it's the toes' turn to pull on the plantar fascia, lifting the arch and twisting and shortening the foot to become a tighter, stiffer spring in preparation for the all-important push-off phase of running. It's almost as if the human foot transforms into its own stiff carbon plate when more propulsive force is needed.

There is an old saying: Use it or lose it.

Mother Nature's masterpiece is now being interfered with by the footwear industry. With the intention of preventing injuries, it is developing innovations that allow injuries to occur in the first place. For example, the renowned Harvard professor Daniel E. Liebermann and his colleagues have analysed how toe-bouncing disables the toe muscles and thus increases the risk of injury. This effect can be observed every day on sneaker owners on the street: Because runners can no longer roll over the big toe, they avoid this torque, which should actually go over the big toe, by turning their foot outwards and significantly overpronating.

And what does the industry do? They build a carbon plate into the midsole so that runners no longer have to use their toe muscles. The foot is thus more or less plastered in one direction, which means that the calf muscles and Achilles tendon no longer have a task and become weaker and weaker. This situation is almost paradoxical.

As soon as a person intervenes at one point, he or she upsets the entire mechanism, which eventually leads to an increased risk of injury. "Use it or lose it" is a saying that is often used in sports. At least the many hobby and recreational runners should give preference to "use it" - and their shoes should support them in this.